Understanding Your Brain as You Age

Part 1 - Living Longer: Why Brain Health Matters More Than Ever

At some point — usually quietly — many of us start paying closer attention to our brains.

Maybe it’s the moment you walk into a room and forget why you’re there. Or when a familiar name takes just a little longer to surface. Or when multitasking suddenly feels harder than it used to. None of this is dramatic, but it’s noticeable. And once you notice it, it’s hard not to wonder what it means.

Is this just normal aging? Is this something I should worry about? And maybe the bigger question: Is there anything I can actually do about it?

The encouraging answer is yes — and probably more than you’ve been led to believe.

We’re living in an era most of our ancestors couldn’t have imagined. Life expectancy has been steadily increasing for generations, and it’s not slowing down. Since around 1840, our average lifespan has climbed at a remarkably consistent pace — a reflection of medical advances, public health improvements, and better nutrition. This isn’t just a statistic. It’s a cultural shift. We’re now living long enough that many of us will spend decades in retirement, and that means we have a new question to ask ourselves:

If we’re going to live longer, how do we make sure we live well?

This isn’t a new idea. People have been noticing long lifespans for thousands of years. In the Old Testament, for example, we read about Methuselah living to 969 years and other figures who reached similarly extraordinary ages. Whether those stories are literal or symbolic, they reflect a human fascination with longevity — and a hope that we can live long enough to see the full arc of our lives.

Today, we have real examples of long-lived people whose lives are documented and verified. The Guinness World Record holder for the oldest verified person was Jeanne Calment, who lived to 122 years old. Other documented cases include Jiroemon Kimura of Japan, who lived to 116, and Sarah Knauss, who reached 119.

These stories aren’t just “wow” facts — they show us that human biology is capable of far more than we sometimes assume.

But here’s the key point: brain aging is not tied to chronological age. Two people can be the same age in years and have very different brain function. One might be sharp, active, and engaged; another might feel foggy, tired, and forgetful. The difference isn’t just luck. It’s a mix of genetics, life experiences, habits, and environment.

And that’s why this topic matters so much. Because longer lifespans mean we have a new responsibility — not just to live longer, but to keep our minds vibrant for the years we have.

Living Longer Changes the Conversation

We are living longer than any generation before us, and those extra years are no longer rare or exceptional. What matters now is not just how long we live, but how well our minds support us through those added decades. Brain health is becoming one of the defining factors of quality of life in a longer lifespan.

That’s where brain health becomes so important. Because living longer isn’t just about adding years — it’s about increasing what scientists call healthspan, the years of life we spend feeling capable, curious, connected, and independent. And a large part of healthspan is our mental life: how clear we feel, how resilient we are, and how well we can enjoy the people and experiences we love.

What We Mean When We Talk About Brain Health

If we’re being honest, “brain health” can feel like a big, vague term. It’s easy to picture a memory test or a scary diagnosis, and then feel like there’s nothing you can do. That’s because when most people hear “brain health,” they think of memory — names, dates, where you put your keys. And yes, memory matters.

But your brain is doing far more than storing information. It’s about the way we show up in our lives. It’s how we focus, how we respond to stress, how we connect with others, and how we stay curious and creative. And the good news is that, in many ways, it’s something we can influence through the choices we make each day.

Brain health is how your mind feels in everyday life. It’s the part of you that helps you stay steady when life feels complicated. It’s what allows you to focus long enough to read a book, follow a conversation, or learn something new. It shapes your mood, your motivation, your curiosity, and even how well you sleep at night.

Brain health shows up in your everyday experience, not just on a memory test. It influences how clear you feel when you wake up in the morning, how resilient you are under stress, and how engaged you feel with the world around you. These changes often happen gradually, which is why they can be easy to dismiss or explain away — we just assume it’s “normal aging.”

Some days your brain feels “on.” Other days it doesn’t. That’s normal. What matters is the trend over time.

What’s important to understand is that many of these functions don’t decline suddenly. They shift slowly, often in response to years of lifestyle patterns. That’s actually good news, because it means they can often be supported — even improved — when those patterns change.

Large reviews of long-term studies — including the U.S. POINTER Study and FINGER trial — consistently show that lifestyle factors like diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management are strongly associated with cognitive aging and dementia risk. In other words, the brain responds to how we live, not just to how many birthdays we’ve had.

That’s what makes this topic so empowering. Because you don’t need to wait for a problem to show up to start supporting your brain. You can start now — with everyday choices that build a more resilient, clear, and joyful mind.

Aging Is Inevitable — Decline Is Not

Let’s start with a truth that’s both simple and powerful: aging is normal. It’s not a failure. It’s not a problem to fix. It’s simply the process of living. And the brain is part of that process.

But here’s the nuance: not all changes in brain function are the same. Some are expected, and some are shaped by lifestyle. Understanding the difference is one of the most empowering things you can do — because it takes you out of fear and into choice.

Brain changes don’t happen suddenly at age 60. They happen gradually over decades, and they show up differently at different stages of life. In your 40s and early 50s, many women notice a slight drop in processing speed, a little more difficulty multitasking, or needing a bit more time to retrieve a word. These changes are common and often tied to shifting hormones, busy life seasons, and sleep disruption — not brain failure.

As you move into your late 50s and 60s, it’s normal to experience slower recall, a bit more mental fatigue, and more sensitivity to distractions. This stage often brings big life transitions — menopause, caregiving, retirement planning, and changing routines. Those things matter. They affect brain performance, not because your brain is “breaking,” but because your life is changing.

In your 70s and beyond, some people notice more “tip-of-the-tongue” moments, a slower pace of learning new things, and less mental stamina for long, complex tasks. But that doesn’t automatically mean decline. Many people in their 70s and 80s remain mentally sharp, creative, and engaged — especially when they keep their brains active and their bodies moving.

Aging Is Not the Same as Decline

Some changes in the brain are a normal part of aging. Others reflect how the brain has been supported—or strained—over time. Understanding this difference helps replace fear with clarity and opens the door to choices that can meaningfully support brain health at any age.

So what is normal aging? Normal aging often looks like slower processing speed, occasional memory lapses, needing more repetition to learn something new, and more sensitivity to stress and sleep loss. But normal aging does not look like a sharp, rapid decline in daily function, confusion that interferes with daily life, losing track of important events or people, or major personality changes. If you notice those things, that’s when it’s wise to seek medical guidance. But for most of us, the changes we experience are subtle and manageable — and often linked to lifestyle and life stress.

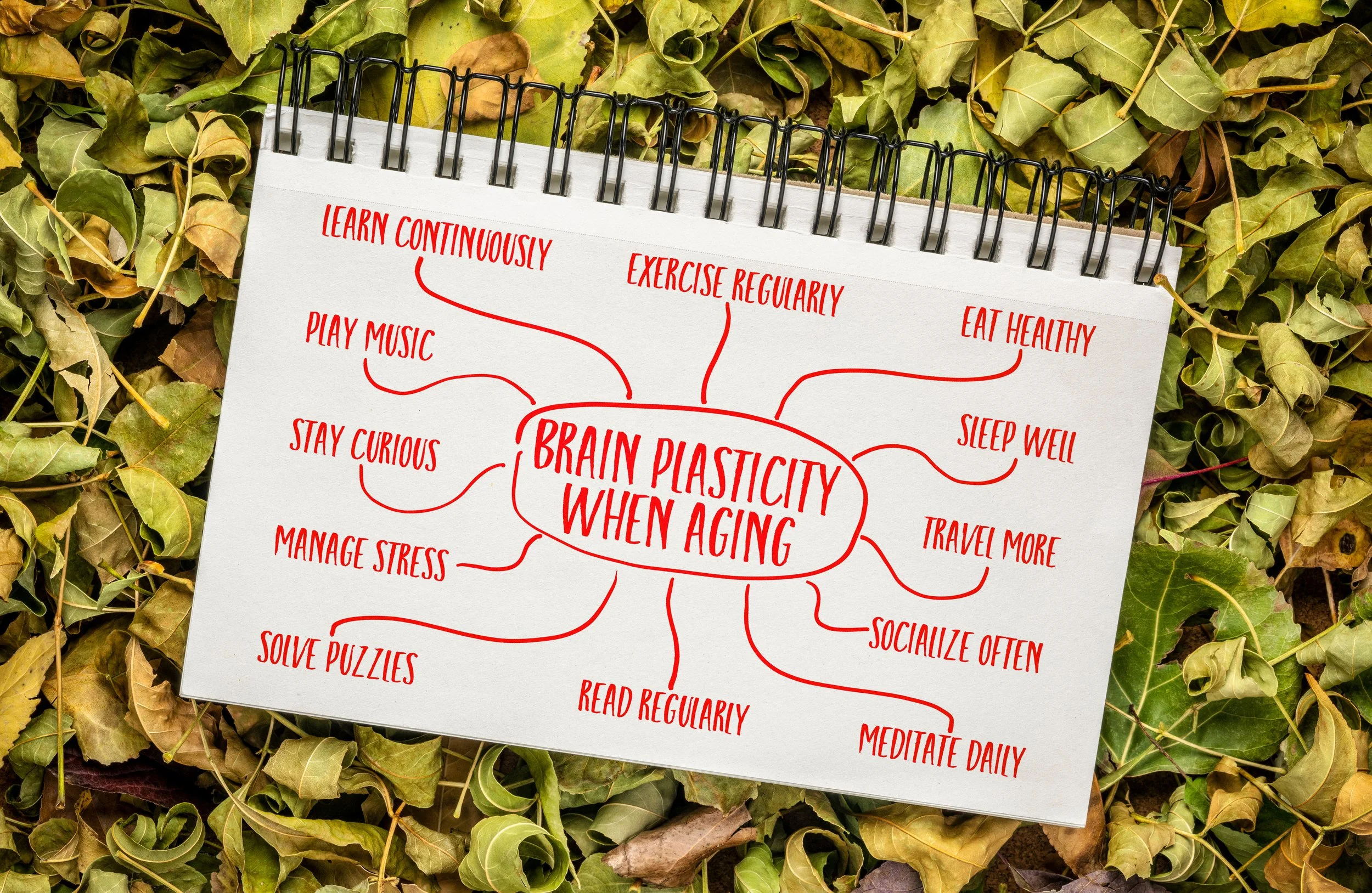

The Aging Brain is Still Adaptable: Plasticity Across the Lifespan

Now let’s talk about the part that gets me excited: brain plasticity.

Plasticity doesn’t mean the brain is flexible like a rubber band. It means the brain is alive and responsive. It continues to adapt throughout life. Every time you learn something new, every time you practice a skill, every time you challenge yourself, your brain is forming new connections.

Think of it like a network of roads. When you repeat an activity, the road becomes smoother. When you stop using a skill, the road becomes less traveled. When you learn something new, the brain builds a new path. That’s plasticity — and it doesn’t stop in your 60s or 70s. It continues.

Research shows that older adults can still form new neural connections and strengthen existing pathways. Learning a new language, practicing music, taking up a new hobby, or even learning new cooking techniques all stimulate the brain and help build cognitive reserve — the brain’s ability to adapt and compensate. This is why it’s so important to keep your mind engaged in meaningful ways. Not to “prevent dementia” (which can feel like pressure and fear), but to build a life that keeps your brain active, curious, and alive.

Stress, Mental Health, and the Brain Over Time

Stress is part of being human. A certain amount of it helps us respond, adapt, and get things done. But when stress becomes chronic — when it lingers day after day without relief — it begins to shape the brain in ways we don’t always recognize right away.

Many women in midlife and beyond carry a quiet, ongoing load. Responsibilities don’t disappear as children grow up or careers shift; they often change form. Caregiving, financial concerns, health worries, and the emotional labor of supporting others can create a background level of stress that feels normal simply because it’s familiar.

But the brain feels it.

What Chronic Stress Does to the Brain

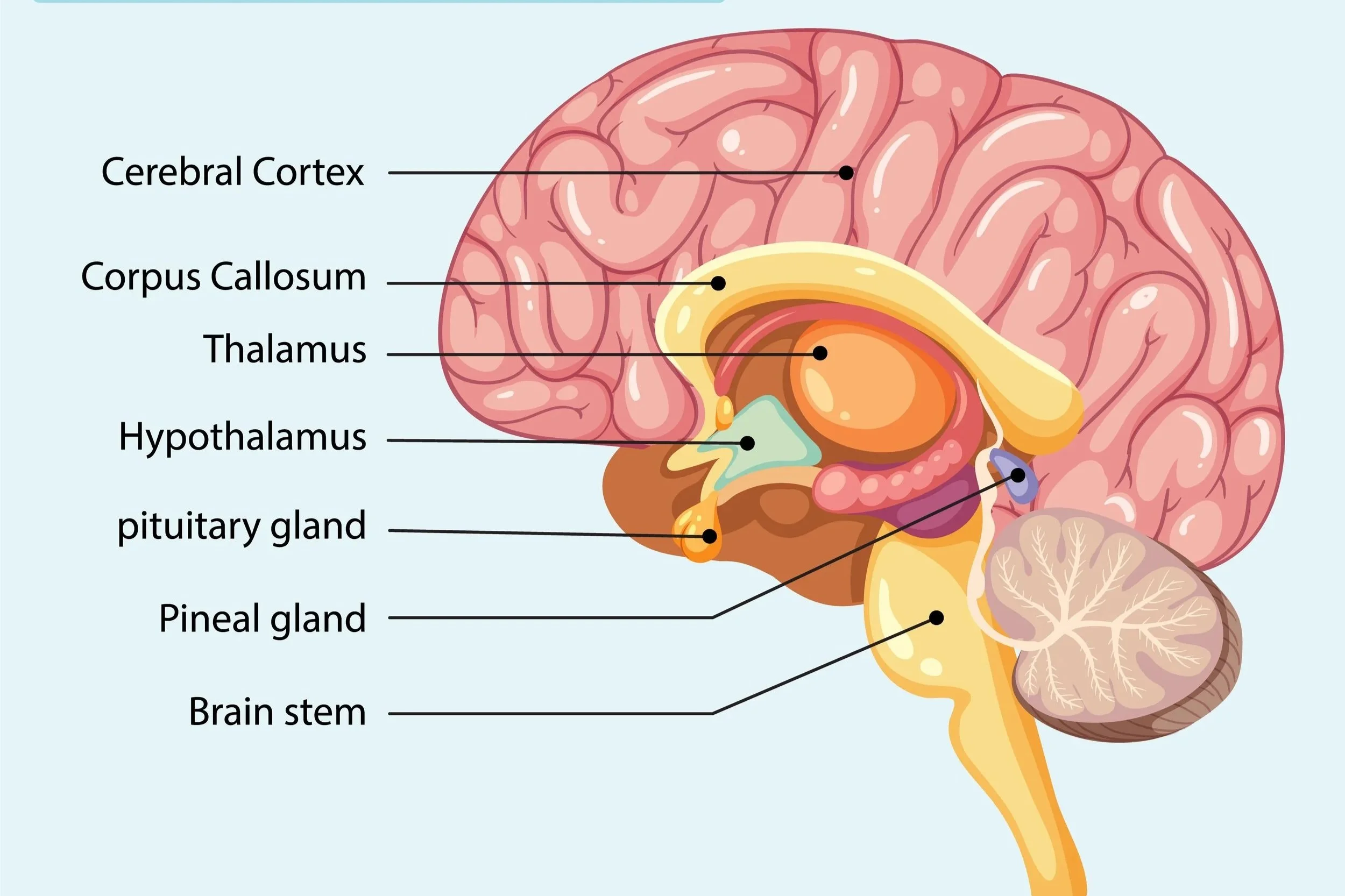

When you’re under ongoing stress, your body releases cortisol, a hormone designed to help you handle short-term challenges. In small doses, cortisol is useful. Over time, though, elevated cortisol can interfere with memory, learning, and emotional regulation.

Chronic stress has been linked to changes in the hippocampus — a region critical for memory — as well as increased activity in the amygdala, the brain’s threat detection center. This combination can make it harder to concentrate, easier to feel overwhelmed, and more difficult to recover emotionally from everyday challenges.

This is why prolonged stress often shows up as brain fog, irritability, low motivation, or feeling emotionally flat. These experiences are not personal failures. They’re signs that the brain has been working too hard for too long.

Stress, Mood, and Cognitive Aging

Over time, unmanaged stress doesn’t just affect how you feel — it affects how the brain ages. Chronic stress and untreated anxiety or depression are associated with increased risk of cognitive decline. That connection is not about weakness; it’s about biology.

Mood and cognition are deeply intertwined. When emotional health suffers, cognitive performance often follows. Supporting mental health is not separate from supporting brain health — it’s central to it.

The Power of Downshifting the Nervous System

One of the most encouraging things about the stress–brain connection is that it’s reversible. The brain is highly responsive to signals of safety. When the nervous system is regularly given opportunities to slow down, the brain can shift out of survival mode and back into repair, learning, and emotional balance. Even small, repeated moments of calm help create a more supportive environment for brain health over time.

Simple practices that calm the nervous system — slow breathing, gentle movement, time in nature, and mindfulness — help shift the brain out of constant alert mode. Even a few minutes of intentional breathing can lower cortisol levels and improve focus.

This doesn’t require meditation retreats or long practices. It requires permission to pause. To stop pushing through. To recognize that rest and regulation are productive.

Mindfulness and Attention as Brain Training

Mindfulness isn’t about emptying your mind or doing it “right.” It’s about paying attention on purpose. When you practice noticing your breath, your body, or your surroundings, you’re strengthening the brain’s ability to regulate attention and emotion.

Studies show that mindfulness practices can improve working memory, reduce emotional reactivity, and support structural changes in brain regions involved in self-regulation. Over time, this builds resilience — the ability to respond rather than react.

Emotional Health as Preventive Care

Supporting emotional health isn’t something you do after you’ve burned out. It’s preventive care for the brain.

Reducing chronic stress doesn’t mean eliminating challenges. It means giving the brain enough safety and support to recover, adapt, and stay flexible.

And when emotional resilience improves, people often notice clearer thinking, better sleep, more energy, and a greater sense of connection — all hallmarks of a healthy brain.

Cognitive Stimulation and Building Cognitive Reserve

One of the most persistent myths about aging is that learning belongs to the young. That once you reach a certain age, your brain is basically set — and any decline is just something you endure.

But the science tells a very different story.

The brain is designed to respond to challenge. It thrives on novelty, complexity, and engagement. When you use your brain in new ways, you’re not just passing time — you’re actively strengthening neural networks and building what researchers call cognitive reserve.

Cognitive reserve is the brain’s ability to adapt, compensate, and continue functioning even when age-related changes occur. Think of it as flexibility and backup capacity. The more reserve you build, the more resilient your brain becomes.

Engagement is Protective

The brain stays healthier when it is used in varied, meaningful ways. Learning, curiosity, and mental challenge help build cognitive reserve — a kind of buffer that supports function even as the brain changes with age. Engagement, not just activity, matters.

Doing familiar tasks is comfortable — and comfort has its place. But the brain changes most when it’s gently pushed beyond what it already knows.

Learning something new forces the brain to form new connections. It requires attention, memory, coordination, and problem-solving, often all at once. This is why activities that feel a little awkward at first — learning a language, playing an instrument, picking up a new craft, or mastering a new technology — are especially powerful for brain health.

That moment of “this is hard” is often the moment your brain is growing.

Reading, Puzzles, and Mental Challenge

Reading regularly has been associated with slower cognitive decline and better verbal skills over time. It engages imagination, memory, and comprehension, especially when you read material that stretches you a bit rather than staying in the same familiar genre.

Puzzles and games — crosswords, word games, strategy games, number puzzles — can also support cognitive function, particularly when they’re varied and challenging. The key is engagement. If an activity feels automatic, it’s no longer doing much for your brain.

Variety matters. Switching between different types of mental challenges keeps multiple brain regions active and communicating.

Bilingualism and Language Learning

Language learning deserves special mention. Research has shown that bilingualism and learning a second language are associated with greater cognitive reserve and delayed onset of dementia symptoms. Learning a new language later in life still challenges the brain in meaningful ways, even if fluency comes slowly.

The effort itself is what matters.

The Unique Power of Music, Creativity, and Art

Creative activities engage the brain in a uniquely holistic way. Music, art, writing, dance, and other creative pursuits activate emotional, sensory, and cognitive networks simultaneously.

Playing music, for example, requires timing, memory, coordination, and listening — all at once. Studies have shown that musical training, even later in life, is associated with structural and functional brain changes.

Creative expression also supports emotional processing, which further reinforces brain health. It’s not about talent. It’s about participation.

Curiosity as a Brain Habit

At the heart of cognitive stimulation is curiosity. Staying curious — asking questions, exploring ideas, trying new experiences — keeps the brain oriented toward growth rather than contraction.

This doesn’t require formal classes or structured programs. It can look like learning a new recipe, exploring a new place, listening to a podcast that stretches your thinking, or having deeper conversations.

The brain responds to engagement. When life feels meaningful and mentally stimulating, the brain stays involved.

Mental Engagement as Daily Practice

Cognitive stimulation works best when it’s woven into daily life, not treated as another item on a to-do list. A little challenge, repeated often, is far more powerful than occasional intense effort.

And like everything else we’ve talked about, it’s never too late to start. The brain doesn’t ask how old you are. It responds to what you ask of it.

Social Connection: Why the Brain Needs Belonging

Humans are wired for connection. It’s not just emotional — it’s biological. The brain evolved in relationship with others, and it continues to function best when we feel socially connected and supported.

As we age, social circles often change. Retirement, relocation, health challenges, caregiving responsibilities, and loss can quietly shrink the number of people we interact with regularly. Many women find themselves feeling more isolated than they ever expected — not because they don’t value connection, but because life circumstances shift.

The brain feels that change.

What Social Isolation Does to the Brain

Research has consistently shown that social isolation and loneliness are associated with higher risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Studies using brain imaging have found links between social isolation and reduced gray matter volume in areas involved in memory, learning, and emotional regulation.

This doesn’t mean being introverted is a problem. Solitude and connection are not the same thing. What matters is whether you feel supported, seen, and engaged — not how many people you know or how busy your calendar is.

Social interaction challenges the brain in subtle but powerful ways. Conversation requires attention, memory, emotional interpretation, and quick thinking. Relationships stimulate multiple brain networks at once, keeping communication pathways active and flexible.

The Brain is a Social Organ

The brain evolved in relationship, and it still responds to connection and belonging. Feeling socially engaged supports emotional regulation, attention, and resilience, while prolonged isolation can act as a form of chronic stress. Connection is not a luxury — it’s part of how the brain stays well.

When you spend time with others, your brain is constantly adapting — reading facial expressions, responding to tone, remembering shared history, and navigating social cues. This kind of stimulation can’t be replicated by puzzles or screens alone.

Social connection also buffers stress. Feeling supported reduces cortisol levels and helps regulate emotional responses. Over time, this protection matters. People who feel socially connected tend to show greater emotional resilience and better cognitive outcomes as they age.

Quality Matters More Than Quantity

It’s not about having a large social network. It’s about having meaningful connections. A few close relationships can be just as protective — sometimes more so — than many superficial ones.

Connection can take many forms: friendships, family relationships, community groups, spiritual communities, volunteer work, shared hobbies, or even regular social routines like walking with a neighbor or meeting for coffee.

What matters is consistency and meaning.

Staying Connected in Practical Ways

Staying socially connected doesn’t always happen automatically. Sometimes it requires intention — especially later in life.

This might mean reaching out first, saying yes more often, or creating new routines that bring people together. It might look like joining a class, volunteering, participating in group activities, or finding online communities that feel genuinely supportive.

For some, it means reconnecting with old friends. For others, it means allowing space for new relationships to form.

The brain responds to connection at any age. Even small increases in social interaction can support cognitive and emotional health.

Belonging and Purpose

Beyond interaction, the brain responds to a sense of belonging and purpose. Feeling useful, valued, and part of something larger supports motivation, mood, and mental clarity.

Purpose doesn’t have to be grand. It can come from mentoring, caregiving, creative work, community involvement, or simply being present for others. When life feels meaningful, the brain stays engaged.

Why Lifestyle Matters: The Evidence in a Nutshell

While aging brings natural changes to the brain, decades of research now show that lifestyle plays a powerful role in shaping how those changes unfold. Brain structure, blood flow, inflammation, and the brain’s ability to adapt are all influenced by how we live day to day.

Across research, three lifestyle factors consistently stand out for their impact on brain health: what we eat, how we move, and how well we sleep.

Dietary patterns rich in whole, minimally processed foods are associated with slower cognitive decline and better preservation of brain structure. Regular physical activity supports blood flow to the brain, encourages the growth of new neural connections, and is linked to lower dementia risk. Adequate, good-quality sleep allows the brain to consolidate memory, regulate mood, and clear metabolic waste that accumulates during waking hours.

These factors don’t operate in isolation. They reinforce one another over time, creating an internal environment that either supports or strains the aging brain. Importantly, their effects are cumulative — shaped by patterns, not perfection.

Understanding this shifts the conversation. Brain health is not determined by age alone, nor is it dictated by any single habit. It reflects the environment we create for the brain to live in over years and decades.

And that brings us to the practical question: how do we support these three pillars in real life?

In Part 2, we’ll take a closer look at food, movement, and sleep — not as rigid rules, but as everyday opportunities to support clarity, resilience, and engagement as we age.

You don’t need a perfect diet or complicated rules to make a difference. Simple, nourishing foods prepared with care can become one of the most practical ways to support brain health as you age.

Roasted Vegetables

These Roasted Vegetables are designed to be simple, adaptable, and deeply satisfying. By roasting at high heat, the vegetables develop caramelized edges and tender centers, allowing their natural sweetness and character to come forward without the need for complicated techniques or finishing steps. A straightforward seasoning blend added before roasting ensures the flavors are well integrated and evenly distributed.

This recipe serves as a reliable foundation rather than a rigid formula. The vegetable mix can shift with the seasons or what you have on hand, while the seasoning options offer subtle variations without overwhelming the dish. Whether you lean toward warm spices, aromatic herbs, or smoky notes, each version keeps the vegetables at the center of the plate.

Roasted vegetables like these fit effortlessly into everyday cooking. They work equally well as a simple side, a base for grain bowls, or part of a larger spread with dips, sauces, or proteins. Easy to prepare and flexible by design, this is the kind of recipe you’ll return to again and again for both weeknight meals and casual gatherings.

Roasted Vegetables

Ingredients

- 8 cups assorted vegetables: cauliflower, broccoli, beets, carrots, red onion, winter squash, sweet pepper, mushrooms, potatoes

- 3 tbsp olive oil

- salt and pepper to taste

- seasoning option 1: 1/2 tsp each coriander, cumin, and garlic powder

- seasoning option 2: 1 tsp smoked paprika, 1/2 tsp dried thyme

- seasoning option 3: 1 tbsp balsamic vinegar, 1/2 tsp dried thyme or rosemary

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 425°F. Line a large baking sheet with parchment paper.

- Toss vegetables in a large bowl with olive oil, salt, pepper, and the selected seasoning.

- Spread in a single layer on the baking sheet.

- Roast for 30–40 minutes, turning once halfway, until tender and caramelized at the edges.

- Serve hot or warm.

Notes

- Cut vegetables into similar sizes for even roasting.

- If using very watery vegetables (like zucchini or mushrooms), space them generously to encourage browning.

- This recipe works as a flexible base for bowls, sides, or shared platters.

Pomegranate Cornbread

Gluten-free Pomegranate Cornbread is a vibrant twist on a classic comfort staple. A 50/50 blend of cornmeal and gluten-free flour creates that perfect, tender crumb while delivering plenty of rustic corn flavor.

Juicy pomegranate arils and whole corn kernels are folded into the batter for pops of sweetness and delicious texture in every bite. Fresh herbs like sage or rosemary add a warm, aromatic note that makes this loaf feel special enough for holidays yet it’s simple enough for busy weeknights.

Serve it alongside chili, roasted meats, or seasonal salads, or enjoy it on its own as a colorful, crowd-pleasing side. It’s a hit every time and folks won’t believe it’s gluten-free!

Pomegranate Cornbread

Ingredients

- 1 cup cornmeal

- 1 cup gluten free flour, with xanthan gum*

- 2 tsp baking powder

- 1 tsp baking soda

- ½ tsp salt

- 1 ½ cups plain yogurt or thick kefir (or dairy free yogurt)

- ¼ cup honey or maple syrup

- ¼ cup melted butter, ghee, or neutral oil

- 1 egg

- 1 cup cooked whole corn kernels (well-drained; fresh, frozen, or canned)

- 1 cup pomegranate arils

- 1-2 tbsp finely chopped fresh sage or 1 tbsp finely chopped rosemary

Instructions

- Heat oven to 375 degrees F. Grease an 8x8 in pan or similar

- In a large bowl, whisk cornmeal, baking powder, baking soda, and salt.

- In another bowl, whisk yogurt, honey, melted butter, egg, and vanilla until smooth.

- Stir wet ingredients into dry just until combined. Fold unicorn kernels, pomegranate arits, and your chosen herb.

- If the batter looks much thicker than a typical muffin batter, loosen with 1-3 tbsp of milk or water so it spreads easily in the pan.

- Scrape batter into the pan, smooth the top and bake for 30-40 minutes, until golden and a toothpick in the center comes out clean. Cover with foil if it browns quickly.

- Cool at least 10 minutes so it sets, then slice.

Notes

- *If your gluten free flour doesn’t have xanthan gum, add ½ tsp with the dry ingredients.

There you have it!

Learning how the brain changes helps us move forward with confidence. Next, we’ll focus on everyday choices that quietly support brain health.