Couscous: More Than a Grain

Last fall, while traveling in Morocco, I sat down to a meal that quietly reshaped how I think about couscous. It was served at a communal table with my tour group in a small restaurant in the High Atlas Mountains, near the Tizi n’Tichka pass—a setting where the landscape itself feels woven into the meal.

The couscous arrived on a wide platter, generously topped with tender vegetables and chicken, the grains beneath light, fragrant, and impossibly fluffy. Surrounding the platter were bowls of green and black olives, a fiery hot pepper condiment, torn pieces of traditional flatbread, and a simple Moroccan tomato and cucumber salad. The meal was unhurried, meant to be shared, passed, and lingered over.

Like many people, I had eaten couscous plenty of times before—but this was different. This was not a quick side dish or a convenient substitute for rice. It was the heart of the meal, prepared with care and rooted in tradition. Sitting there, it became clear that couscous is not simply an ingredient—it is a reflection of place, culture, and the rhythm of daily life.

Couscous is often treated as a shortcut food—something quick to soak, fluff, and serve when time is short. It’s commonly mistaken for a grain, casually labeled as a side dish, or folded into salads without much thought. But couscous deserves more attention than that. Behind those tiny granules is a long history of craftsmanship, shared meals, and culinary intention that stretches back centuries.

At its heart, couscous is not just an ingredient. It is a culinary practice, a cultural symbol, and a reminder that food has always been about more than convenience. To understand couscous fully, we have to look beyond the box and into the kitchens, communities, and customs that shaped it.

What Exactly Is Couscous?

Despite its reputation, couscous is not a grain. It is a form of pasta made from semolina wheat, traditionally created by moistening coarse semolina flour and rolling it by hand into tiny granules. These granules are then dried and later cooked by steaming.

What sets couscous apart from other pastas is its size and cooking method. Rather than being boiled, traditional couscous is gently steamed—often multiple times—allowing it to become light, fluffy, and separate while absorbing the flavors rising from the dish below.

In many ways, couscous sits at the intersection of pasta, grain, and dumpling. It’s small enough to behave like a grain in cooking, yet its structure and preparation firmly place it in the world of pasta.

A Brief History of Couscous

Couscous traces its roots to North Africa, particularly the Maghreb (Arabic for “West”) region, which includes present-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, and the Western Sahara. Its origins are commonly linked to Berber communities, where couscous was developed as a practical, nourishing food well suited to arid climates and communal living.

Historically, couscous was prepared by hand—often by groups of women working together. The rolling of semolina into uniform granules was time-consuming and precise, a process that reinforced both skill and social bonds. This wasn’t everyday convenience food; it was an expression of care and tradition.

Couscous also played an important social role. It was frequently served on Fridays, holidays, and family gatherings, presented on large communal platters meant to be shared. Over time, trade routes, migration, and colonial influence helped spread couscous across the Mediterranean and into Europe, where it was embraced and adapted into new culinary contexts.

Today, couscous is found on tables around the world, but its cultural roots remain deeply tied to hospitality, generosity, and shared experience.

Couscous Around the World

While couscous remains a staple in North African cuisine, it has taken on many forms globally.

In Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, couscous is often served beneath slow-simmered vegetables, legumes, and meats, with broths ladled generously over the top. In France, couscous has become a beloved comfort food, frequently paired with roasted vegetables and grilled meats.

Across the Mediterranean and beyond, couscous appears in chilled salads, stuffed vegetables, and modern grain bowls. Its neutral flavor and adaptable texture allow it to absorb regional influences while still maintaining its identity.

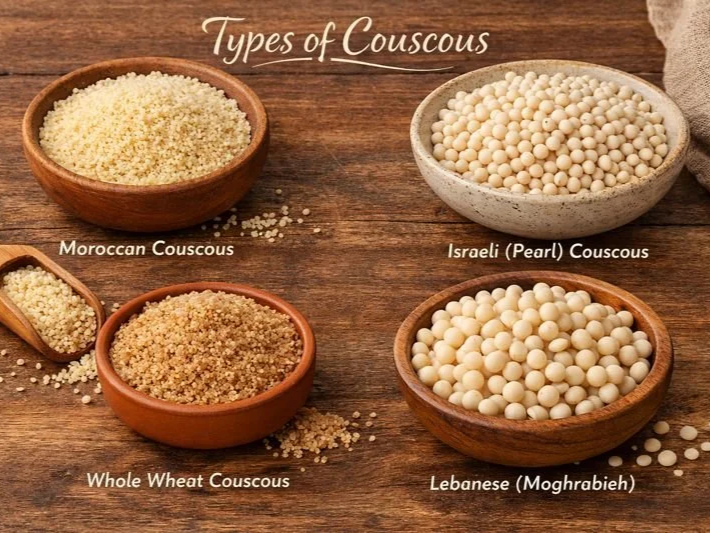

The Different Types of Couscous

Not all couscous is the same. Size, texture, and culinary use vary widely depending on the style.

Moroccan Couscous The smallest and most delicate variety, Moroccan couscous is what most people picture when they hear the name. Fine and quick-cooking, it becomes light and fluffy when properly prepared. Traditionally steamed, it pairs beautifully with vegetables, stews, and aromatic broths.

Israeli (Pearl) Couscous Also known as pearl couscous, this variety is much larger, with round, pea-sized grains. It is often toasted before cooking, giving it a slightly nutty flavor and a pleasantly chewy texture. Pearl couscous works well in warm dishes, pilafs, and salads where a more substantial bite is desired.

Lebanese Couscous (Moghrabieh) The largest of the couscous family, moghrabieh resembles small chickpeas. It requires longer cooking and is traditionally served with hearty broths, chicken, and onions. Its size makes it feel more like a dumpling than a grain.

Whole Wheat Couscous Made from whole wheat semolina, this version has a deeper color and a more pronounced wheat flavor. The texture is slightly heartier, making it a good choice for rustic dishes and warm bowls.

How to Make Couscous: Traditional and Modern Methods

Couscous can be prepared in a range of ways, from time‑honored traditional steaming to the quick methods most of us use today. Understanding both approaches helps explain why couscous can taste so different depending on how it’s made.

Instant or Boxed Couscous (Quick Method)

This is the most common method outside North Africa and works well for everyday cooking.

Instant couscous is pre‑steamed and dried, which means it only needs to be rehydrated.

Place couscous in a heatproof bowl.

Bring water or broth to a boil and pour it over the couscous.

Cover tightly and let it rest.

Fluff gently with a fork to separate the grains before serving.

This method is fast and convenient, but flavor depends heavily on the liquid used and proper resting time.

Traditional Steamed Couscous (Couscoussier Method)

In traditional North African cooking, couscous is prepared in a couscoussier, a two‑part pot with a stew or broth simmering below and couscous steaming in the top (shown in picture above).

The process typically includes:

Lightly moistening dry couscous with salted water and a small amount of oil

Steaming the couscous over simmering broth

Removing it, fluffing by hand, and breaking up clumps

Sprinkling again with water and returning it to steam

Repeating this process two or three times until tender and airy

This multi‑step approach produces couscous that is exceptionally light, separate, and infused with the aromas rising from the dish below.

Helpful Tips for Better Couscous

Liquid‑to‑couscous ratio: Most instant couscous works well with a 1:1 ratio, but check the package and adjust slightly for texture.

Use stock instead of water: Vegetable or chicken stock adds depth without extra effort.

Avoid clumps: Pour liquid evenly, don’t stir immediately, and fluff only after resting.

Resting matters: Let couscous sit covered for at least 5 minutes so it can fully absorb liquid.

Fluff gently: Use a fork, lifting rather than stirring, to keep grains separate.

The Traditional North African Couscous Spice Palette

One of the reasons traditional North African couscous tastes so deeply satisfying—despite couscous itself being quite neutral—is the intentional use of spices in the broth and toppings, not the grains alone. Couscous is designed to absorb flavor, acting as a soft, receptive base for the layered aromas rising from below.

Rather than relying on a long list of spices, traditional couscous cooking focuses on a relatively small core, with each spice playing a clear role. Together, they create warmth, color, depth, and balance without overpowering the dish.

Core Warm Spices (The Foundation)

These spices build the savory backbone of the couscous and its broth.

Cumin

Flavor: Earthy, warm, slightly bitter

Job: Anchors the savory base of the dish and gives the broth a distinctly North African character rather than a generic Mediterranean flavor.Ginger (ground)

Flavor: Warm with a gentle sharpness

Job: Adds warmth and structure to the broth, especially in chicken-based couscous, without introducing chili heat.Turmeric

Flavor: Earthy, slightly bitter

Job: Provides the golden color associated with festive couscous and adds subtle background warmth that ties the dish together.Cinnamon

Flavor: Sweet, woody, and aromatic

Job: Creates sweet–savory contrast, particularly when paired with meat, onions, and dried fruit, as in couscous topped with tfaya.

Color and Aroma Builders

These spices enhance visual appeal and aroma while rounding out the flavor profile.

Paprika (sweet)

Flavor: Mild, gently sweet, sometimes smoky

Job: Adds warmth of color and soft sweetness to tomato-based sauces, meats, and broths.Black Pepper

Flavor: Sharp and pungent

Job: Provides subtle heat and lifts the warmth of cumin and ginger without dominating the dish.Saffron

Flavor: Delicate, floral, slightly hay-like

Job: Used sparingly in special or celebratory couscous—often with chicken—to perfume the dish and add refined aroma.

Heat and Depth

These elements add complexity and allow heat to be adjusted to taste.

Harissa, Chili, or Cayenne

Flavor: Fruity heat with lingering warmth

Job: Introduces controlled spiciness, often added to the broth or served on the side so each person can adjust heat individually.Ras el Hanout

Flavor: Deeply layered, warm, slightly sweet

Job: Used sparingly to add complexity and cohesion, bringing together individual spices into a unified flavor profile.

Fresh Herbs and Finishing Touches

These ingredients brighten the dish and balance the richness of the warm spices.

Cilantro (Coriander) and Parsley

Flavor: Fresh, green, lightly citrusy

Job: Stirred in at the end or sprinkled on top to lift the dish and add freshness.Mint

Flavor: Cooling and aromatic

Job: Used more often as a garnish or in lighter preparations, mint brightens couscous and pairs especially well with dried fruit and nuts in sweeter variations.

Together, these spices and herbs explain why traditional couscous tastes layered and complete: each component has a purpose, and none is meant to stand alone.

Savory Couscous Recipe Ideas

Moroccan-Style Vegetable & Chicken Couscous Steamed or hydrated couscous topped with tender chicken, carrots, zucchini, chickpeas, and onions simmered with warm spices. Finished with fresh herbs and a ladle of fragrant broth.

Caramelized Onion & Chickpea Couscous Pearl couscous tossed with deeply caramelized onions, chickpeas, olive oil, and a pinch of cumin and coriander. Excellent as a main or hearty side.

Mushroom & Garlic Pearl Couscous Toasted pearl couscous cooked in vegetable stock and finished with sautéed mushrooms, garlic, and thyme. Rich, earthy, and comforting.

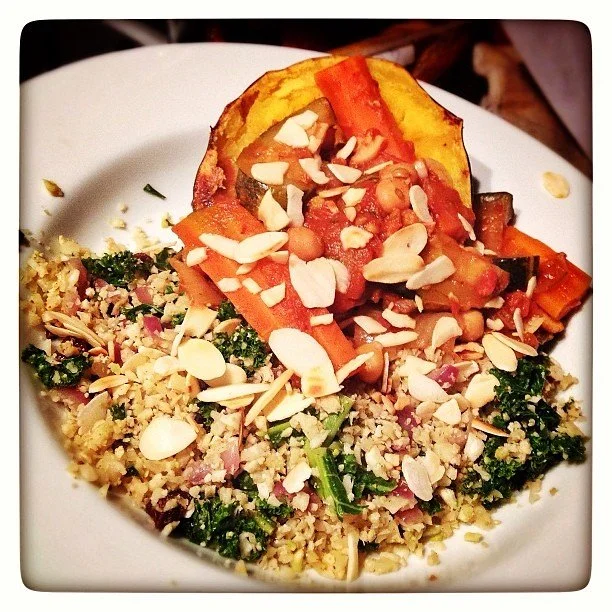

Roasted Vegetable Couscous with Herbs Fluffy couscous folded with roasted squash, tomatoes, and red onion, then finished with parsley, mint, lemon zest, and olive oil.

Warm Couscous with Greens Couscous gently mixed with sautéed greens, garlic, and a splash of broth or olive oil for a simple, nourishing bowl.

Sweet Couscous Recipe Ideas

Breakfast Couscous with Fruit & Nuts Couscous warmed with milk or plant-based milk, lightly sweetened, and topped with fresh or dried fruit and toasted nuts.

Cinnamon-Spiced Couscous with Dates Lightly sweetened couscous infused with cinnamon and finished with chopped dates and almonds.

Orange Blossom Couscous Couscous gently scented with orange blossom water, folded with raisins or dried apricots, and finished with pistachios.

Pearl Couscous Pudding Pearl couscous simmered slowly in milk until tender and creamy, then finished with honey, vanilla, and a pinch of spice.

Maple & Apple Couscous Warm couscous tossed with sautéed apples, maple syrup, and a touch of cinnamon for a comforting breakfast or dessert-style dish.

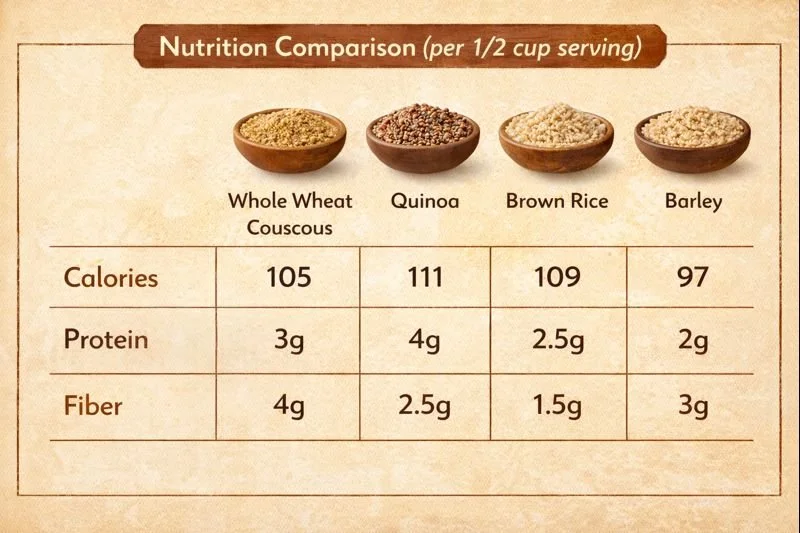

Whole Wheat Couscous: Nutrient-Dense Whole Grain

It provides fiber, plant protein, B vitamins and minerals, and higher intakes of whole grains like whole wheat couscous are consistently associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, some cancers, and all‑cause mortality. Its specific benefits relate to gut health, metabolic health, satiety and weight management, and cardiometabolic risk markers.

Digestive and gut health Whole wheat couscous typically provides about 340–355 kcal, 63–71 g carbohydrate, 11–13 g protein, and around 10–11 g fiber per 100 g dry (generous 1/2 cup), plus small amounts of fat and sodium.

This fiber content is substantially higher than refined couscous and contributes meaningfully toward daily fiber recommendations that are linked with lower chronic disease risk. Whole‑grain fibers act as prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut bacteria and supporting a more diverse microbiome, which is linked to better immune function and lower systemic inflammation.

Metabolic health and blood sugar Compared with refined grains, whole grains (including whole wheat products similar to couscous) are associated with lower fasting insulin, better insulin sensitivity, and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

One study reported that additional servings (≈50 g) of whole grains per day was linked with ~20% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with very low intakes.

Cardiovascular and longevity benefits A large BMJ meta‑analysis of prospective cohorts found higher whole‑grain intake was associated with significantly lower risk of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and all‑cause mortality, with benefits evident from about 1–3 servings per day upward.

Satiety, weight management, and micronutrients Whole wheat couscous’s combination of complex carbohydrate, protein (≈11–13 g/100 g dry), and fiber (≈10–11 g/100 g dry) promotes fullness and can help reduce overall energy intake when used in place of refined grains.

Whole wheat couscous also contributes minerals such as selenium and magnesium; selenium acts as an antioxidant and supports thyroid function, while magnesium is important for glucose metabolism and blood pressure regulation.

Couscous Compared to Other Staples

Compared to rice: Couscous cooks faster and has a lighter, fluffier texture, though nutritionally they are fairly similar.

Compared to quinoa: Quinoa contains more protein and is naturally gluten‑free, while couscous offers a more neutral flavor and softer bite.

Note: Because couscous is made from wheat, it contains gluten. It is not suitable for people with celiac disease or gluten intolerance, who may prefer alternatives such as rice, quinoa, or gluten‑free grains. There are also gluten free options available that are made from quinoa, millet, brown rice, or corn.

Did You Know?

Couscous was added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list in 2020, recognizing its role in community life and shared traditions.

Traditional couscous-making tools have been found in North Africa dating back over a thousand years.

In many cultures, couscous is eaten from a shared platter, reinforcing the idea of food as a communal experience.

The word “couscous” is believed to come from the Berber word seksu, referring to the sound made when rolling semolina between the hands.

Ras el Hanout: Morocco’s Signature Spice Blend

Ras el hanout is less a recipe and more a philosophy.

Often translated as “head of the shop,” ras el hanout represents the very best spices a spice merchant has to offer. It is not a fixed blend, nor is it meant to taste the same from one kitchen—or even one market—to the next. Instead, it reflects place, season, tradition, and the personal hand of the person who blends it.

In Moroccan cooking, ras el hanout is used sparingly, but its impact is unmistakable. A small pinch adds warmth, depth, and complexity, giving dishes a layered flavor that feels both grounding and a little mysterious.

What Is Ras el Hanout?

Ras el hanout is a complex North African spice blend most closely associated with Morocco, though variations exist throughout the Maghreb, including Algeria and Tunisia. Unlike standardized spice mixes, ras el hanout has no single authoritative formula. A blend may contain anywhere from a dozen to more than thirty spices.

Historically, each spice seller created their own signature version, often using their freshest and most prized spices. In this way, ras el hanout functioned as both a culinary tool and a statement of quality—a way for a merchant to say, this is my best.

Ras el hanout is not meant to be spicy-hot. Instead, it is aromatic and balanced, built around warmth rather than heat.

You might notice:

Earthy depth from cumin and turmeric

Gentle sweetness from cinnamon and paprika

Floral or citrus notes from coriander or cardamom

A lingering warmth rather than a sharp finish

Its complexity is subtle. Rather than dominating a dish, ras el hanout creates a sense of cohesion, helping individual ingredients taste more complete.

Common Spices Found in Ras el Hanout

While no two blends are exactly alike, many share a familiar core. These spices work together to build warmth, aroma, and gentle sweetness.

Cumin – Earthy and grounding; anchors the blend in savory cooking.

Coriander – Lightly citrusy and floral; softens heavier spices.

Ginger – Warm and gently sharp; adds heat without chili burn.

Cinnamon – Sweet and woody; rounds out savory dishes beautifully.

Turmeric – Earthy and slightly bitter; provides golden color and background warmth.

Black pepper – Sharp and pungent; adds quiet structure.

Paprika – Mild and slightly sweet; enhances color and depth.

Some blends also include cardamom, cloves, nutmeg, allspice, mace, dried rose petals, or grains of paradise. Historically, rarer or luxurious ingredients reinforced ras el hanout’s reputation as a showcase blend.

A Spice Blend With a Sense of Place

Ras el hanout reminds us that spice blends were once deeply personal. They reflected local tastes, seasonal availability, and the instincts of the cook or merchant who created them.

Like couscous itself, ras el hanout connects everyday meals to tradition, place, and the quiet art of building flavor slowly and intentionally.

Simple Ways to Use Ras el Hanout

Season chicken, lamb, or vegetables before roasting

Add a pinch to soups or stews for depth

Stir into couscous or rice cooking liquid

Mix with olive oil as a marinade base

Use sparingly with lentils or chickpeas

A small amount is all you need—this is a spice meant to whisper, not shout.

Moroccan Mint Tea: A Gesture of Hospitality

No Moroccan meal feels complete without mint tea. Often prepared with green tea, fresh spearmint, and sugar, it is poured from high above the glass to aerate and cool it, creating a light foam on top. More than a beverage, mint tea is a gesture of welcome—served before or after meals, offered to guests, and shared slowly in conversation.

The sweetness and freshness of mint tea provide a gentle counterpoint to richly spiced dishes like couscous, extending the experience beyond the plate and reinforcing the sense of connection at the table.

How Moroccan Mint Tea Is Made

Traditional Moroccan mint tea begins with green tea—most often Chinese gunpowder tea—rinsed briefly to soften its bitterness. Fresh spearmint is added generously, along with sugar, and the tea is steeped until fragrant. Rather than stirring, the tea is poured into a glass and then back into the pot several times to blend and aerate it. Finally, it is poured from a height into small glasses, creating a light foam on top. The result is a tea that is sweet, fresh, and aromatic, meant to be sipped slowly and shared.

A Simple Home Version

To make Moroccan-style mint tea at home, bring water just to a boil and steep green tea for 2–3 minutes. Add a generous handful of fresh mint (preferably spearmint) and sweeten to taste with sugar or honey. Let it steep briefly, then pour the tea into a mug or glass, lifting the kettle or teapot slightly as you pour to mimic the traditional aeration. The flavor should be fresh and lightly sweet, offering a cooling contrast to warmly spiced dishes like couscous.

Couscous as Connection

Couscous is more than a grain or a technique—it is a way of gathering. Traditionally served from a shared platter, it invites people to slow down, lean in, and eat together. The careful layering of spices, the gentle steaming of the grains, and the long-simmered broth beneath all reflect a rhythm of cooking that values patience and presence.

I was reminded of this while sharing couscous at a communal table with my tour group in the High Atlas Mountains, near the Tizi n’ Tichka pass. The meal felt generous, grounding, and deeply connective - rooted in the simple act of eating together.

That is the enduring beauty of couscous. It adapts to what is available, reflects the hands that prepare it, and turns everyday ingredients into something meant to be shared. Whether cooked traditionally in a couscousier or prepared more simply at home, couscous carries with it a sense of place, hospitality, and connection—one that lingers long after the last bite.

7 Vegetable Moroccan Couscous with Chicken

This 7 Vegetable Moroccan Couscous with Chicken is a comforting, traditional-inspired dish built around tender chicken thighs, chickpeas, and a colorful mix of vegetables gently simmered in a fragrant, ras el hanout–spiced broth. It reflects the heart of Moroccan couscous cooking, where depth of flavor comes from layering spices, slow simmering, and careful timing rather than complicated technique.

The vegetables are added in stages so each one keeps its texture and character—root vegetables and squash first, followed by cabbage and chickpeas, with zucchini added at the end. The chicken cooks slowly in the broth, becoming tender while enriching the sauce that’s spooned over the couscous at the table.

Served over whole wheat couscous and presented family-style, this dish is meant to be shared. With its aromatic broth, generous vegetables, and warm spices, it’s a satisfying meal that works just as well for a relaxed gathering as it does for a cozy weeknight dinner.

7 Vegetable Moroccan Couscous with Chicken

Ingredients

- Chicken & Broth

- 4 bone-in, skin-on chicken thighs

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 1 cup onion, thinly sliced (1 medium)

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 2 tsp ras el hanout

- ½ tsp ground turmeric

- ½ tsp freshly ground black pepper

- 5 cups chicken broth or water

- Vegetables & Legumes

- 1 cup cooked chickpeas (canned, drained and rinsed)

- 2 carrots, cut into large chunks

- 1 small rutabaga, peeled and cut into wedges

- 1 small acorn squash (or butternut pumpkin), cut into wedges

- ½ small green cabbage, cut into wedges

- 1 medium zucchini, cut into thick quarters

- Couscous

- 1 ¼ cups whole wheat instant couscous

- 1 ½ cups hot chicken broth (from the pot)

- 4 tsp olive oil or melted butter

Instructions

- Season chicken thighs well with salt and pepper. Heat olive oil in a large, heavy-bottomed pot over medium-high heat. Brown chicken on both sides until deeply golden, about 4 minutes per side. Remove and set aside.

- Lower heat to medium. Add sliced onion to the pot and cook until soft and lightly golden, scraping up any browned bits. Stir in garlic, ras el hanout, turmeric, and black pepper. Cook 30–45 seconds until fragrant.

- Return chicken thighs, and any collected juices, to the pot. Add broth and bring to a gentle simmer. Cover partially and cook for 20 minutes, skimming foam if needed.

- Add carrots, rutabaga, and winter squash. Cover, bring back to a simmer and cook for 10 minutes.

- Add cabbage wedges. Cover, bring back to a simmer and cook another 10 minutes.

- Add zucchini and chickpeas. Cover, bring back to a simmer and cook another 10 minutes. All the vegetable should remain tender but intact.

- Taste and adjust salt.

- Place whole wheat instant couscous in a large bowl. Stir in olive oil or butter and a pinch of salt so that all the grains are evenly coated. It should look like wet sand. Ladle hot broth over the couscous, cover tightly, and let steam for 5 minutes. Fluff gently with a fork.

- Spread couscous onto a serving platter. Arrange chicken, vegetables, and chickpeas on top. Spoon some of the aromatic broth over everything, serving extra broth on the side. Garnish with fresh herbs and offer harissa separately.

Notes

- When adding the vegetables, bury under the vegetables so they're submerged while cooking.

- In Moroccan homes, couscous is often served communally, with broth spooned over gradually so everyone can adjust moisture to taste.

Apple Whole Wheat Couscous Pudding

Baked Apple Whole Wheat Couscous Pudding is a cozy, spoonable dish that sits somewhere between a classic baked custard and a gently set bread pudding—only lighter, fruit-forward, and free from refined sugar. This dish highlights simple ingredients and gentle technique, letting flavor and texture do the work.

Diced apples are sautéed slowly in butter and cinnamon until just tender, concentrating their natural sweetness and adding depth before they’re folded into the pudding. The custard base—made with milk, eggs, vanilla, and warming spices—bakes into a soft, creamy interior that holds together beautifully while staying delicate and moist.

It’s equally suited to breakfast, brunch, or a not-too-sweet dessert, especially when served warm with a drizzle of maple syrup, a spoonful of yogurt, or a splash of milk. It reheats well, making it a lovely make-ahead option for slow mornings or casual gatherings.

Apple Whole Wheat Cous Cous Pudding

Ingredients

- 1 cup whole wheat couscous

- 1 ¼ + ¼ cup milk of choice (dairy, almond, or oat milk)

- ½ cup water

- 3 medium apples, cored, and diced

- 2 tbsp unsalted butter

- 2 large eggs (or 1/2 cup silken tofu for vegan version)

- 4 tbsp maple syrup or honey (adjust to taste)

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 1 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1/4 tsp ground nutmeg

- 1/4 tsp ground ginger

- Pinch of salt

- 2 tbsp chopped nuts (walnuts, pecans, or almonds)

- 1–2 tbsp raisins or chopped dates (optional)

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C). Lightly butter an 8x8-inch baking dish.

- In a skillet over medium heat, melt butter. Add diced apples, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and a pinch of salt. Cook for 5–7 minutes until apples are tender but still hold their shape. Stir in 1–2 tbsp of the maple syrup or honey if you want extra sweetness. Remove from heat.

- In a small saucepan, bring 1 ¼ cup milk, water, the rest of the maple syrup or honey vanilla, and a pinch of salt to a gentle simmer. Remove from heat, stir in couscous, cover, and let sit for 5 minutes until tender. Let cool slightly.

- In a bowl, whisk eggs and remaining milk. Gradually stir in the warm couscous, then fold in the sautéed apples and raisins/dates if using.

- Pour mixture into the prepared 8x8-inch baking dish. Sprinkle nuts on top. Bake for 28–32 minutes, until the pudding is set but still slightly jiggly in the center. A knife inserted in the middle should come out mostly clean.

- Let cool for 5–10 minutes before serving. Top with yogurt, a dash of nutmeg, and a drizzle of maple syrup or honey if desired.

- Enjoy warm as a cozy breakfast or dessert.

Notes

- Extra creamy: Use 1/4 cup cream or coconut cream with the milk.

- Flavor boost: Add 1 tsp orange zest while sautéing apples for a bright note.

- Make ahead: Cover and refrigerate for up to 3 days; reheat gently.

There you have it!

Couscous is humble, adaptable, and deeply rooted in tradition. Cook it simply, season it thoughtfully, and let it do what it has always done best—bring people together.